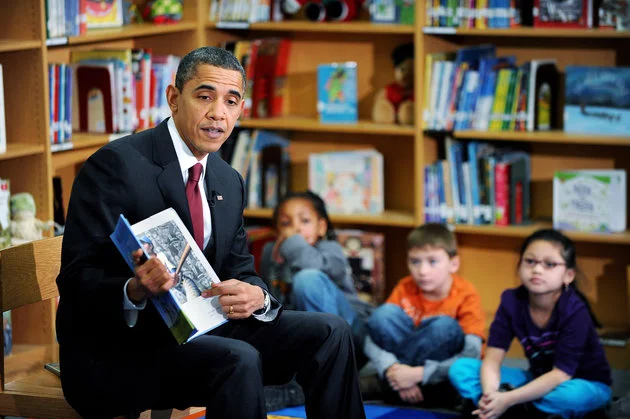

At eleven and six, President Barack Obama has been the only president my sons have consciously known. My oldest doesn't remember the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries first-hand, but from my retelling he’s adopted a personal memory of toddling along with me to vote for Obama at our DC voting station a field away from our neighborhood playground. I should probably tell him how he and I walked around the National Mall to the U.S. Capital days before crowds descended to witness with sheer jubilation Obama's inauguration. How thrilling it was to see the preparations unfold, how uplifted and joyful I felt. How optimism and hope sparkled in the cold sun. It’s a source of pride for my big boy to have lived in DC then and participated in that historic moment, just as it’s a source of pride for my little boy to have been born with Obama in the White House. To them, President Barack Obama is their president, and they’re sad to see him leave office. As am I. To remind them that Obama will always be their president, I've pulled a few biographies off our shelf.

Barack Obama: Son of Promise, Child of Hope By Nikki Grimes. Illustrated by Bryan Collier (Simon & Schuster 2008)

Barack by Jonah Winter. Illustrated by AG Ford (Harper Collins 2008)

When we read about young Barack, I ask my sons if they, particularly my older one, can relate to his story. Like their president did as a child, they've lived abroad. Like their president's, their parents are from different countries. Like their president, they’ve had to adjust to new environments at a young age, to find their place in new schools, to straddle different realities. Like their president, my older one knows what it’s like to be an outsider, how painful it can be and how much pluck, courage, and determination it takes to move past challenging moments. They’ve both had early training in resilience building, like their president. I wonder how this awareness will shape their view of themselves and their sense of place in the world. I also wonder if they will remain avid readers and have that too in common with President Obama, our Reader-in-Chief and Commander of Books.

In addition to rereading books about their president, we’ve been rereading one by him. Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters (Random House, 2010), gorgeously illustrated by Loren Long, is a loving, patriotic celebration of some of America's exceptional sons and daughters whose achievements reveal an inner quality -- creativity, intelligence, bravery -- that rests within the children for whom the book was written, Sasha and Malia, and every single child to whom the book is read.

Whenever we read a book, we occupy someone else’s expressive space. I tell my kids it’s kind of like we’re actually inside the author’s head, experiencing their creative imagination up close. When I read Of Thee I Sing to my sons, I’m keenly aware that my reading voice is blending with Obama’s storytelling voice. It’s a magical moment that connects my sons directly to their president. When I read the questions Obama’s narrative voice asks throughout the book, I’m aware that my reading voice joins a chorus of readers who ask children they love the same type of rhetorical question, one that often begins with “Have I told you…

… that you have your own song?

… that you are strong?

…that you are kind?"

Reflecting Obama’s prodigious intellect, the title Of Thee I Sing is an elegant expression of American history and its bold spirit. The line “Of Thee I Sing” is the third in the opening stanza of Samuel Francis Smith’s patriotic hymn “America.” Smith was a young Baptist seminarian at Andover Theological Seminary when he wrote the lyrics c. 1831. He was inspired to write a patriotic song while translating the German song, “God Save the King.” Smith’s lyrics were set to the same music as the German piece, which dates to the early eighteenth century, and which remains that of the British National Anthem. Known also as “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,” and rather less inspiring as United Methodist Church Hymn 697, it was our country’s unofficial national anthem until the “Star Spangled Banner” was officially adopted in 1931. In this way, Obama’s Of Thee I Sing is set firmly in America’s European, Protestant past. It is also grounded in civil unrest.

In 1864, while the country was split and at war with itself, Smith sent his song upon request to J. Wiley Edmands, who had served as Massachusetts State Representative from 1853-1855. Reflecting the troubled spirit of the time in his letter to Edmands, Smith writes that he is “happy to have been the means through [his lyrics] of adding a momentary joy to a festive, or light to a gloomy hour.” It strikes me that Obama’s Of Thee I Sing has added joy to our lives and is right now a light during what for my sons and me is a gloomy hour.

The last line of the opening stanza in Smith’s hymn can be related directly to our nation's struggle for civil rights. I want to make sure that when my sons listen to the words “Let freedom ring” they hear Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s resounding voice. Of Thee I Sing helps me to pass this to them when I read to them, "Have I told you that you don't give up?"

In Of Thee I Sing, Obama also offers a lesson in “how important it is to honor others’ sacrifices,” like Maya Lin did when she designed the Vietnam Memorial. The book urges my sons to be inspiring, like Cesar Chavez, and to boldly explore, like Neil Armstrong. In the question, “Have I told you that you are a healer?” we are asked to be mindful where we walk because we tread upon land claimed for us at a tragic cost of life.

If the least representational, the rendering of Sitting Bull as the land itself is perhaps the most evocative of Loren Long’s illustrations. It’s beautiful, and sad, and troubling because we don’t see a Native American as much as we see an idea of a historical figure. That alone speaks volumes about the erasure of our tragic past my sons aren’t yet ready to even begin to confront. Yet, Obama’s words strike a somber chord, too, and unite many strains to the brutal past of American history. On the two-page spread dedicated to Sitting Bull, Of Thee I Sing echoes the second stanza in UMC Hymn 697: “My native country, thee, land of the / noble free, thy name I love; I love thy / rocks and rills, thy woods and templed hills; / my heart with rapture thrills, like that above.” I wonder if one day this spread will rest somewhere in my sons’ consciousness. I wonder if its imprint will inform their understanding of heritage? Will the natural landscape we claim as our national heritage be connected to stolen lands and loss of life?

Without exception, the two-page spread in Of Thee I Sing my sons linger over every time we read it together comes at the end.

The boys hover over the pages spread open on my lap. They study the children’s faces to identify the grown-ups they become. When they do this, my sons are experiencing the power of their president’s aspirational legacy. This is Obama’s enduring “Yes, we can” message penned just for them. What a gracious and generous gift.

The back story suggested on every page Of Thee I Sing I’m most curious to discover is the one that will reveal how Loren Long came to illustrate President Obama’s picture book. It’s poetic and fitting that the illustrator of Watty Piper’s beloved Little Engine That Could has given visual expression to Obama’s optimistic vision of America and its big-hearted folks.

Of Thee I Sing is full of grace and filled with hope. If we had the chance, we'd ask President Obama “Have we told you that you make us proud?”

Thank you, Mr. Obama, for serving with humility, guiding with hope, and leading with honor. You will always be my sons’ first president.